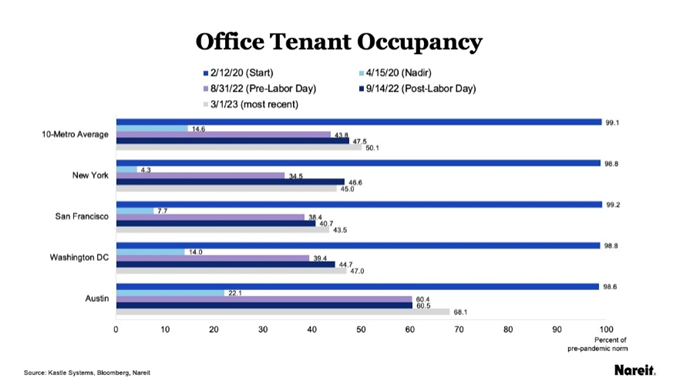

Working from the office in the US has lost its appeal for many, leading to questions over the future of the asset class. Robin Marriott reports. (long form article)

MAGAZINE: A difficult new world

- In Magazine highlights

- 20:48, 24 mei 2023

Premium subscriber content – please log in to read more or take a free trial.

Events

Latest news

Best read stories

-

Weekly data sheet: Motel One sale's valuation is latest proof of hospitality sector roaring back

- 12-apr-2024

Morgan Stanley spin-off, Proprium, made a 20-times multiple on its €65 mln equity investment in 2007 in Motel One.